I can read.

Beauty books that I enjoyed and want you to also, as well.

One hazard I am constantly negotiating (resisting) as a writer is the reputation that we’re all big readers. We’re reading all the time when we’re not talking about writing or about being a writer. This was true of me when I was a minor (I also did not have nearly as many friends then, so). I would spend entire weekend afternoons in my local library in the YA stacks, reading books cover to cover while sitting on that stained, low-pile carpeting. (Pretty sure I read The Princess Diaries that way, as well as Angus, Thongs, And Full-Frontal Snogging.)

I’ve gotten very bad at reading in my adult life because I apparently would rather spend my time endlessly scrolling instead. And then I feel productivity guilt, like I should be writing instead of reading or doing anything else that could lead to something. The only times I can sit the fuck down and read whole chapters in a row is in the spring/summertime when I can sit outside in the sunshine. Reading is an outdoor activity for me. That’s how I got through the entire Animorphs series (that’s 54 books) in the first summer of the pandemic.

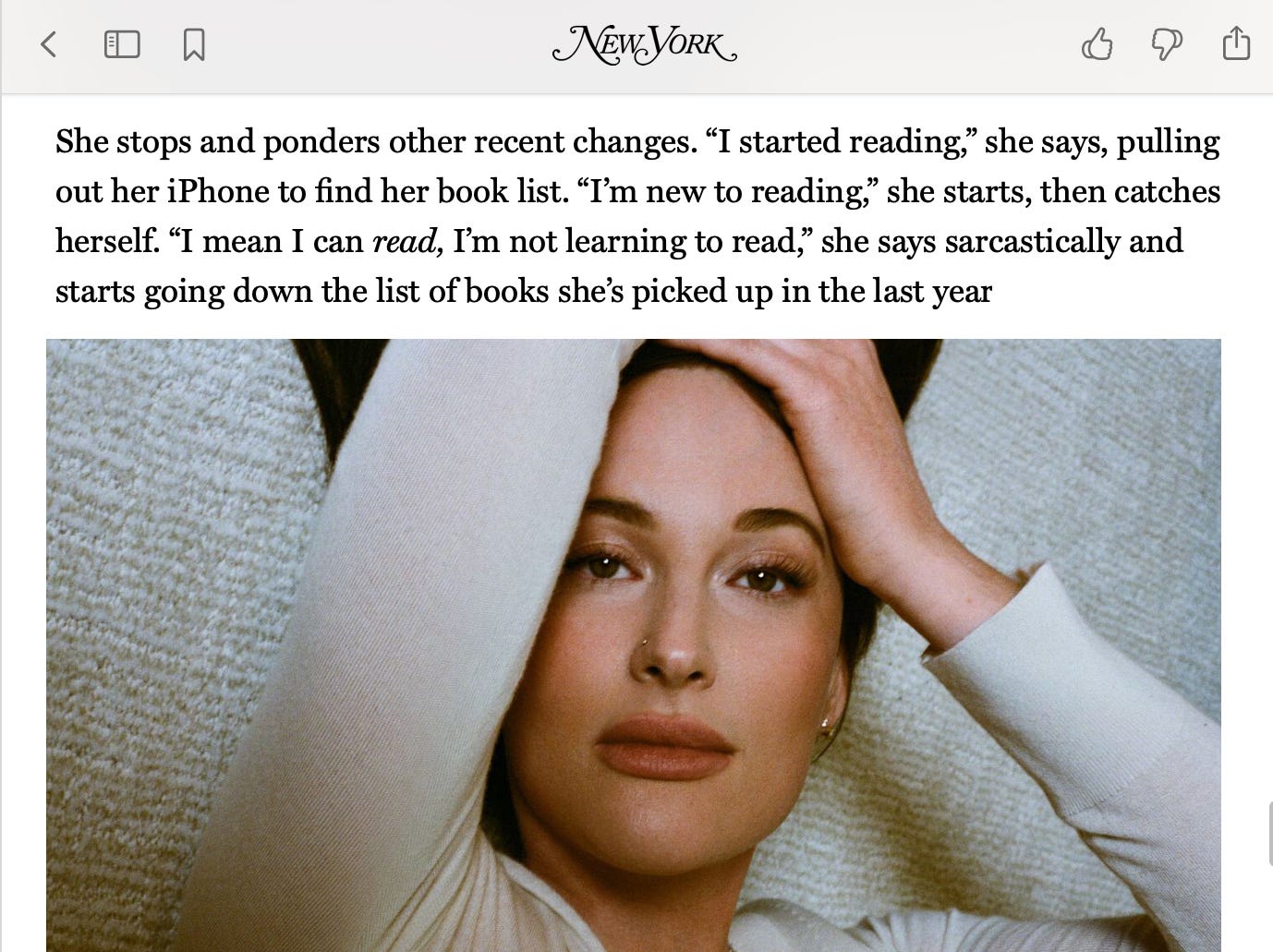

I relate very much to this tidbit from The Cut’s profile of Kacey Musgraves, in which she too can read. The stars, they’re just like us!

Reliable literary bait for me is a beauty book for obvious reasons. There are so many people much smarter than me who have explored the forensic, philosophical, and intellectual depths of beauty culture, feminism, and appearance-based sociology. And it all fascinates me. I mean, we can agree on many things, like the stressy and opressy pressures of beauty culture today, the alienating forced normalization of medical aesthetics, the con of empowerment through product-based wellness and self-care, and the paranoia and anxiety of the nonstop look-a-thon that our current social media panopticon inspires — you get it. Or you feel it. The why behind it is what keeps me exploring.

Examining beauty (and other body/appearance politics) from a broad range of perspectives that involve other people’s lived experiences — people who don’t look like you and don’t share the same cultural experiences as you — can only give you a better understanding of the reaches of beauty’s impacts.

So. Here are some beauty books that I derived great pleasure, insight, and sunshine from. I hope you do as well.

Thick and Other Essays by Tressie McMillan Cottom

I love me some TMC. Tressie McMillan Cottom is a lot of things (professor at UNC, New York Times columnist, MacArthur fellow) but a bullshitter is not one of them. I discovered her very illuminating and wry TikTok on my FYP, and then went on to read a NYT op-ed of hers about the politics of blond (the backlash from the argument within got her banned from the app temporarily). She is blunt in a way that I find comforting, coming from a long line of blunt women in my family. Hard things said softly is my preferred delivery method, which she nails in a way that makes you go “It was there all along!” (The way that one searches for their sunglasses only to realize that they’ve been sitting on top of their head the whole time… or something like that.)

The kick-off essay in Thick goes beyond examining beauty’s validity by measuring out who and what is responsible for ugliness.

For beauty to function as it should, it must exclude me. Big Beauty—the structure of who can be beautiful, the stories we tell about beauty, the value we assign beauty, the power given to those with beauty, the disciplining effect of the fear of losing beauty you might possess—definitionally excludes the kind of blackness I carry in my history and my bones. Beauty is for white women, if not for all white women. If beauty is to matter at all for capital, it can never be for black women. But if I believe that I can become beautiful, I become an economic subject. My desire becomes a market. And my faith becomes a salve for the white women who want to have the right politics while keeping the privilege of never having to live them. White women need me to believe I can earn beauty, because when I want what I cannot have, what they have becomes all the more valuable. I refuse them.

When I say that I am unattractive or ugly, I am not internalizing the dominant culture’s assessment of me. I am naming what has been done to me. And signaling who did it.

I am glad that doing so unsettles folks, including the many white women who wrote to me with impassioned cases for how beautiful I am. They offered me neoliberal self-help nonsense that borders on the religious. They need me to believe beauty is both achievable and individual, because the alternative makes them vulnerable. If you did not earn beauty, never had the real power to reject it, then you are as much a vulnerable subject as I am in your own way. Deal with that rather than dealing with me. Compared with the forms of oppression they can now see via their proximity to me, it may seem to privileged people that it is easier to fix me than it is to fix the world. I live to disabuse people of that notion.

To sum it up: "Beauty isn’t actually what you look like; beauty is the preferences that reproduce the existing social order.”

Disobedient Bodies: Reclaim Your Unruly Beauty by Emma Dabiri

I learned of Disobedient Bodies from this Dazed feature on Emma Dabiri. What I love about this book is how elegantly and compassionately Dabiri lines out beauty’s intricate contradictions, recognizing beauty’s institutional and historical dilemmas alongside the complicated feelings we all share that keep us from getting around them. One thing that always irks me about a lot of theoretical beauty criticism is how it disregards the very thing that keeps us at it — Emotion™!

I get it, emotional arguments are rarely tolerated by critical analysis. They are fickle, stubborn, petulant, and often ego-driven. And nobody wants to deal with a sour ego. But we must oblige them if we are to reconcile our relationship to beauty and ourselves. Disobedient Bodies is a quick read — I downed it in one go. When it ended I felt that pang of grief when a good book ends. I wished it was longer but I also think it’s fine that books are short when they are as impactful as this one.

According to the logic of ‘consumer choice’, cosmetic surgery is recommended for improving self-esteem, while discourse is wedded with the missive that we ‘love ourselves just the way we are’. All of these new innovations and their complicated pleasures have distorted already indistinct boundaries between beauty operating within a system of oppression, and beauty as an expression of agency and autonomy. Market relations have become ever more fully a part of our relationship to our bodies and what we ‘choose’ to do with them. Yet our choices arguably only reproduce the prevailing logic. Choices within an oppressive or exploitative paradigm aren’t always as liberating as we might want to think.

I also love this critique of hers on the trick of inclusivity:

That inclusion is the best solution that we can seemingly come up with powerfully illustrates the need for fresh thinking. I don’t want to fight to be appreciated as an object. I want to transform the world in which objectification of women is the default. I don’t believe the solution to making beauty – as it’s currently understood, as an abstracted, singularly visual, physical quality – less oppressive is merely to diversify those standards, to expand them to include fat, black, brown, short, and disabled bodies.

Flawless: Lessons in Looks and Culture from the K-Beauty Capital by Elise Hu

I’ve been listening to Elise Hu on numerous podcasts for some time, and this TED Radio Hour episode is where she talks about the intense beauty ideals of South Korea, and how beauty has become a national export as well as a means of global soft power — all at the expense of its citizens who are pressured to be “flawless.” Not just pressured, they are socially and economically punished for not adhering to these rigid beauty standards.

Hu lived in South Korea for many years, as NPR’s Seoul bureau chief, which is the premise of Flawless. In it, she explores beauty from the unique lens of Korean history, technology, and culture while making it relevant to today’s hyper-fixation on appearances. It is interesting to learn about Korean culture from this sociological Asian-American perspective, and how so many things that I assumed were unique idiosyncrasies of the maternal side of my family come from this fundamental Koreaness. To this day, I still don’t understand a lot of it (which has a lot to do with not knowing the language, I’m sure).

Flawless explores (briefly) how war influences beauty. The reason we have cosmetic surgery is because of war and its violence on the human body — the earliest facial reconstruction techniques were developed to repair the disfigurement done to veterans’ faces in combat.

One of Korea’s most popular aesthetic procedures, the blepharoplasty (aka double-eyelid surgery) was developed in the late 19th century by a Japanese doctor, but its popularization and racialization were established in large part thanks to a U.S. Marines chief plastic surgeon stationed in South Korea during the Korean War, who developed his blepharoplasty technique on Korean sex workers wanting to appeal to American GI clients. As far as the Western perspective was concerned, the “oriental eye” needed amending for a face to be accepted as fully human [*dry heaves*].

When you consider how granular beauty flaws can be today, you can’t forget that to a large swath of civilization, these minute physical features are the difference between humanity and wholesale dehumanization.

I asked her whether she considered cosmetic surgery “gendered violence,” as some academics call it. She considered for a beat. “Yes,” she finally responded, without elaborating. “Why?” I followed. “It’s like marriage,” she said. “Some people consider marriage very natural. You know, not all married women are miserable or unhappy. So . . . it doesn’t mean women who take cosmetic surgery are victims or anything like that.” Of course not, I said. You choose it. “Maybe this is just wordplay,” she said, “but I don’t think having choices is free will. Maybe all choices we make are related to, are affected by, the system. So I don’t really like [the binary] free choice vs. structure. I think our choices are all structural. I would say . . . I mean, even when I choose my cell phone, like Samsung over iPhone, I don’t think that’s my free choice.”

Under the theory of French philosopher René Girard, humans are extremely good at mimicking one another, and we learn what we desire, and what to desire, based on what our neighbors do. “We assume that desire is objective or subjective, but in reality it rests on a third party who gives value to objects,” he wrote. “This third party is usually the one who is closest, the neighbor.”

Our current standards are not just unachievable, they’re mostly arbitrary. The plastic surgery clinics keep trying to apply math or science to quantify beauty: to pin it down, put a number on it, and arrive at a perfect ratio or “golden mean.” But these standards are too often solutions in search of problems.

Made-Up: A True Story of Beauty Culture Under Late Capitalism by Daphné B.

I could not put Made-Up down once I started it. So much of this book is lushly textured, cinematic even, in its descriptions and feelings on beauty. The author addresses her vulnerabilities and curiosities regarding beauty with a moody and philosophical existential yearning while racking up Sephora VIB Rouge points. It’s thrilling in the way a Lana Del Rey music video montage is thrilling. And just as poetic.

I have never known capitalism to be anything but an economic (and geopolitical) dilemma, but Made-Up unfolds all the ways that it holds our deepest longings for ransom. DB is well aware of beauty’s manipulative and exploitative nature, and she also regards beauty practices — its idleness and desirous indulgence — as a form of personal resistance against cultural demands for productivity at all hours. She respects the constructs of beauty, that it demands spending time with yourself and connecting with your corporeal form (how you wish to spend that time is up to you).

Makeup is the pivotal device in this book — it contains multitudes! Of colors, of class, coded feminization, stigmatized vanity, self-decoration, sheer wonder and delight, and of course, of economy. You have never read about makeup until you have read about makeup from a French-Canadian poet.

To reduce makeup to the level of a pumpkin spice latte – to spit on the whole cultural practice of it as if makeup alone summed up the failures of our entire civilization – is a subtle means of gendering it. From there, you’d practically have to consider capitalism itself feminine, in a sort of neo-Genesis retelling of the sexist Garden of Eden story. Don’t we castigate capitalism for the same sins we castigate femme fatales for? (Or women, period.) Using artifice and sex to excite, then sending the bewitched plunging into the abyss? Like a witch, capitalism is powerful, dangerous, and incapable of love, all too often dooming those under its spell to self-doubt and precarity. Its only moral code is selfishness and the fulfillment of its own desires.

And on how beauty’s stigmas are a response to the threat that women inherently pose:

Like makeup, bleach is an artifice that allows you to transform, to alter your identity. But attempting to make use of this forbidden power is a risky business. Changing one’s identity throws a wrench in the order of things, because the construction of social ties depends on the stability of certain figures. By upsetting these ties, bleach subverts them. Blonde jokes – or any other form of humiliation that peroxidized women endure – stem in part from an attempt to restore social order. They’re being punished for the freedom they’ve granted themselves, the audacity they’ve had in modifying and sexualizing their appearances. So if we’re cruel to them, if we call them sluts, if we laugh while their locks burn off, so be it.

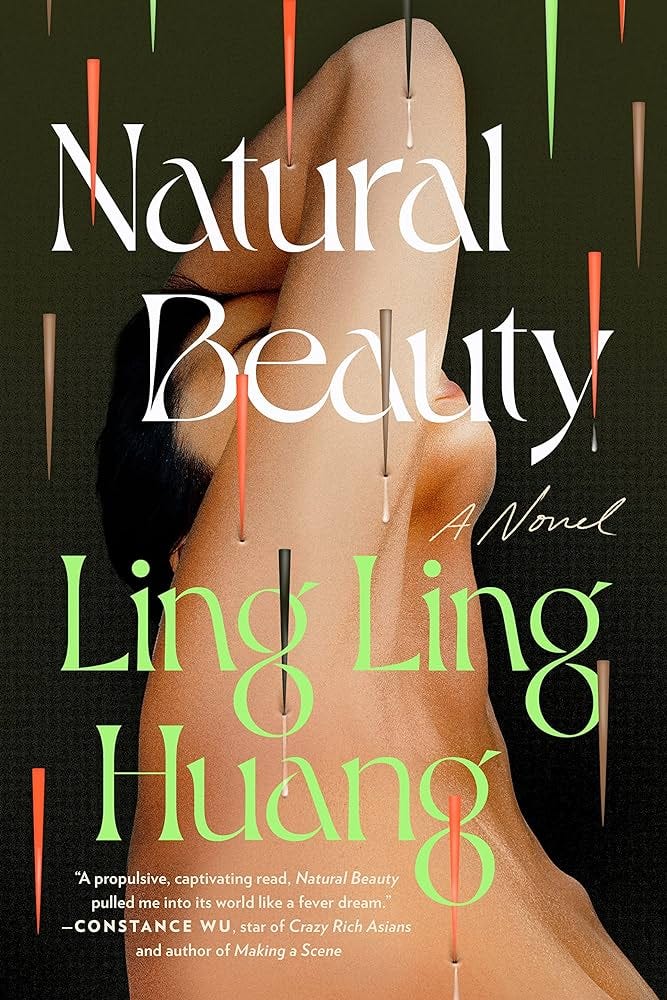

Natural Beauty by Ling Ling Huang

The one novel in my very abbreviated syllabus is Natural Beauty by Ling Ling Huang. I love a horror treatment for beauty stories because so much of beauty practices are quite frankly, horrific. This novel has everything: classical music, heart-wrenching familial relations, mean boarding school kids, new york city, bitchy shop girls, nice shop girls, rich girls, poor girls, annoying roommates, a mysterious mansion, PTSD, lesbians, so many jars, a horrible realization, and monsters.

Tl;dr: A piano prodigy child grows up and takes a job at the hypiest luxury beauty/wellness shop, Holistik (Goop sun, Tesla rising, Soylent moon) in NYC to help pay for her parents’ care after they’re in a bad accident. As an employee, she partakes in all of Holistik’s supplements, powders, and treatments, only to discover, as they transform her appearance in a very mythical white kind of way (think Galadriel), the horrific secret sauce within.

The only unrealistic thing in this novel was the unconditionally loving and supportive relationship the protagonist had with her Chinese parents regarding her career as a professional concert pianist. (But that may be my personal bias as a failed pianist and a disappointment to mine. Parents, I mean.)

We want to learn how to better serve our customers. The more we learn, the more we can anticipate their desires. Technology is the biggest blessing in that way. Good or bad, we all want to be absolved of our choices.

“Victor’s smart. He knows where there’s culture, there’s counterculture. Every established beauty norm has an equal and opposite reaction, right? He may not agree with other definitions of beauty, but he certainly wants to profit from them.”

I enjoy the immense freedom that comes with being safe from desire. And it is a kind of power to embrace ugliness and its possibility of expression, so much more imaginative than beauty.

Incomplete mentions

Some beauty books intrigued me by their premise and after reading, found them… not for me. I do think that reading views that challenge your own can sometimes be a great way to examine your own biases (and what is more biased than beauty?) but sometimes all it provides is validation for my opinions and beliefs.

Of course, The Beauty Myth by Naomi Wolf is one of the most-mentioned books on beauty in recent times, and I wanted to see what all the fuss was about, but tbh I did not find it compelling from the jump. And then the author started telling on themselves in the most embarrassing way, by tweeting anti-vax conspiracy theories (that got her banned from the platform), and how children who wore protective face masks lost the ability to smile (???). Nevermind!

The premise of Perfect Me: Beauty As An Ethical Ideal interested me in its examination of beauty as an ethical ideal. According to my Kindle, I’ve stopped at 36% through, but it honestly feels like I’ve been chewing on this for ages. A lot of it builds on and repeats itself, and every chapter has its own unnecessary intro that has at least seven pages of in this essay I will… (literally, “In this chapter I will”).

It is a laborious read. The author, Heather Widdows, is a British philosopher, which I was made to remember many times throughout the analysis of beauty in this book and the number of times “indeed” punctuated and preceded so many sentences. I mean, there are some nuggets of knowledge in there but your eyeballs will be extracting them with a shovel. (The Goodreads reviews are brutal.) It’s a dry, academic perspective on a select history of beauty culture. Maybe the other 64% is where the excitement is, but I think I’m good.

Ok, now your turn. (Please tell me of the beauty books that you appreciated and think I would appreciate as well, thank you.)

Not sure if this counts as a "beauty book" per se, but if you liked Thick, maybe check out Belly of the Beast by DaShaun Harrison, which also tackles the intersection of racism, fatphobia, gendered violence, and conventional standards of attractiveness.

oh wow, THANK YOU! i’ve been looking for beauty books to read, but my local library picks are abysmal. searching online gave very mixed results and how SEO-driven websites described them made me wary.

this is everything i wanted. thank you again!!!

fellow commenters: book club!? hahahha